|

|

|

PhotoShop Basics for

Photographers

|

|

When it comes to digital photography (and that includes scanning

your slides/negatives/prints into digital as well as acquiring them

in digital with a camera) nothing beats Photoshop as the other

"half" of your camera.

It's pricey and worth every penny. Loaded with features

(many of which you'll never use) it also has extremely easy to use

functionality that will dramatically improve each and every

photograph you take.

Because it's such a deep program and because it can do a whole

lot more than "simply" improving scanned or taken digital

images, the usual basics of Photoshop that are taught or written

about leave a lot of beginning photographers bewildered and

wondering if they made a mistake in buying Photoshop. So

here's the crash course (and everything you need to know to get your

photos looking picture perfect).

(Note: while the menus will be somewhat different, these

techniques apply equally to Photoshop Versions 4 through 6.01.

I will refer to the 6.01 menus but if you have any difficulties

working out the process in any other version feel free to email us

here).

|

|

Choosing your Output |

|

The absolute first decision you need to make is where your image

is going. This will affect a lot of your choices down the

road.

The two main choices are output to print, and output for the

web. They differ in resolution -- for print we want to keep as

many pixels as possible, and for the web we'd like to discard as

many as possible.

What I normally do is prepare a web sized image and then if I

decide to create printed output I'll go back to the original and

work from there. If the thought of making two separate sets of

adjustments drives you crazy (and you have need of both web and

print versions) then make a version targeted for print and use

Photoshop's Save for Web menu item (off the File menu) on

that. You won't be getting an optimum web shot, but it will be

close.

|

|

Output

for Print |

|

If your target is your printer then your number 1 priority is

saving as many of those precious pixels as possible while printing

at the size desired.

To do that we need to get familiar with two Photoshop dialog

boxes: the first is Image/Image Size.

Image Size allows you to adjust the printed height and width of

an image. It does this is two distinct and very different

ways: it will either adjust the resolution (pixels per inch) of the

image, or it will resample the image.

Resampling for print is very very bad. Repeat after me:

resampling for print -- just say no. I want to repeat this

several times and elaborate on this because this might be contrary

to what you've heard (or read) elsewhere.

When Photoshop (or any other program, for that matter) resamples

downward (that is, creates a smaller image) it will be discarding

those precious pixels we need and love. Those pixels are what

give detail to our image, so it's pretty obvious that we do not

want to discard any of them.

When Photoshop resamples upward it's even worse -- here PS is

"guessing" at what pixels might or should be there.

Like any computer, it's not very good at guessing (computers are

much better when they "know" something, as opposed to

guessing at it). PS resamples upward pretty good, not as good

as a dedicated program like Genuine Fractals (which makes a living

doing that kind of guessing) but you don't need to use either PS or

Genuine Fractals.

The secret is that you already have software that will be doing

the resampling for you, and doing it much better than any outside

program can do. It's called your printer driver, and it knows exactly

how much resolution it needs to print the best. In the case of

photo printers, which are optimized to work with the best resolution

they need, no other program can know in the same way what's best for

your printer -- trust me.

So how do we make the image the size we want without resampling?

Just uncheck that box in Image Size. Now you see that you no

longer have the ability to enter the number of pixels you'd like (up

above) but only the width, height and/or resolution of your image

down below.

Don't enter the resolution -- that will only buy you a certain

width and height. We want to specify exactly how big we want

our print, and our printer driver will do the rest.

Since it should go without saying you want to leave Constrain

proportions on (unless you're going for a funhouse effect) you'll

note that you can only adjust either the height or the width

but not both. The only trick here is to preserve those precious

pixels, so you need to adjust the dimension that ends up the

smallest. So, for example, if you want to adjust a landscape

shot (an image shot with the largest dimension running horizontal)

then you adjust the height for the dimension you want (since it's

the smallest). Let's try an actual example.

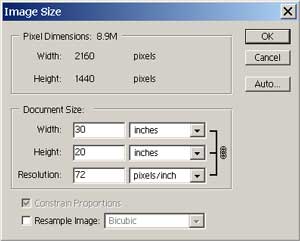

Here we have the number of pixels the Canon D30 produces in a

landscape shot, 2160 x 1440, which at the default resolution of 72

pixels per inch produces a 20 x 30 inch print.

That's probably too big for most of your printers, and in this

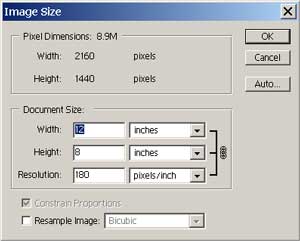

case we'd rather do something a little smaller, like 8x10. So

we adjust the smallest dimension (the height) downward to 8 inches

(which is the smallest dimension on our print size).

Now we end up with an 8x12 inch print, which is right in the

ballpark now. Notice the resolution has increased, to 180

pixels per inch, but we don't really care about that.

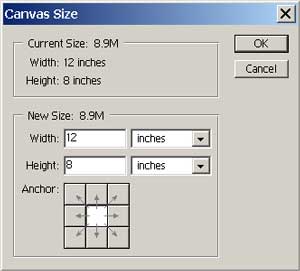

We need to get rid of those two extra inches, and to do so we

need to crop them out, using another Photoshop dialog. After

saying okay here we go to Image/Canvas Size.

This is where you can crop your image down to size.

Remember, we don't want to discard any pixels we don't have to, but

in this case we have too many pixels in one direction to print on a

common print size. The image is too wide, so we enter 10 in

the width size. If we were to say okay here PS would (after

warning us) chop off an inch off each side.

If we want to keep one side we can use that funny looking nine

square box called Anchor. Selecting either the middle right or

middle left square will preserve the right or left of the image

accordingly. Then the entire two inches will come off the

other side.

If you've been composing correctly you'll usually use the middle

default anchor, but there are times you want to tweak a

little. What if you'd like to chop off 1/2 inch on the left,

and 1 1/2 inches on the right? Just use the Canvas size dialog

twice -- the first time enter 11 inches in the width box and select

the left most middle box. This will chop 1 inch off on the

right. Now enter Canvas Size again and put 10 inches for

width, but leave the anchor in the middle. Now you've chopped

another inch off, equally divided between the right and the left (or

an additional 1/2 inch on the right and 1/2 inch on the left).

One last thing you should know about image size and output -- not

all file formats save the pixels per inch information. If you

were to save the image as a TGA, for example, after setting it up to

print at 8x12 and then brought it back in again the pixels per inch

setting would have changed, and you'd be printing that 20x30 inch

monster. TIF preserves this information, as do some other

formats.

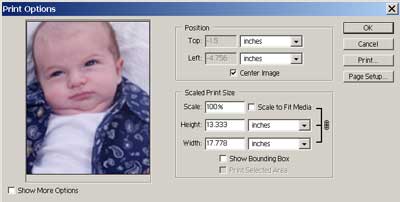

Someone asked recently if using the Print Options menu (not

available on versions of PS prior to 5) would result in the same

thing as the above process.

The answer is a qualified yes -- you can use Print Options (see

below for dialog box) as it does exactly the same thing as adjusting

the dimensions -- that is, it will adjust the resolution

independently. So why bother learning about the above?

The simple answer is you really don't -- except there are times

it will be helpful to understand the process. Because there is

no way of seeing the pixels and resolution you are adjusting here,

you really can't see what's going on. Because we really can't

print at resolutions that are too low it's helpful to

understand just how large you can make any image before you reach

that threshold. If you are only working with a set of images

for which you are familiar with the resolution (you always shoot a

certain camera, and it always produces a certain resolution) you can

safely ignore the image adjustment procedure and use Print

Options. But like with any shortcut you only take it as long

as you are familiar with the long way around (otherwise you'll get

lost).

|

|

Output

for Web |

|

For the web our problem is the exact opposite -- we want the

fewest pixels possible that still produce a good image.

That's because we all don't have DSL in our homes just yet, and

the smaller the image the faster it will load (and we're all

impatient on the web). The good news for those of you using PS

5.5 or greater is that Photoshop has automated this process with

their File/Save for Web routine.

You'll still need to crop for artistic purposes if desired (and

you have more latitude here, because unlike for print you're going

to have way too many pixels to begin with, so any cropping you do

just makes the discarding that much easier). In this case we

want to reverse our process and use the Image/Canvas Size dialog

first. We crop as desired and then we go to File/Save for Web.

In that dialog you'll be giving a bewildering amount of options

and possibilities, but you really only need to consider two

things -- how big an image you want, and what degree of JPG

compression you want to apply.

I would recommend for the compression medium, nearly

always. Most people can't tell the difference at any higher

levels, and medium is a good compromise for loading

times.

Size is completely up to you. Since most people are still

not using monitors with anything more than SVGA resolution (800x600)

you'll only be making people do a lot of scrolling if you make your

image any larger in either of those two directions. Further,

remember that those are the absolute limits of the monitor -- put an

image in a browser program and you've further reduced the pixels

available to you. Unless you just like making most people mad,

I'd stick with 600x400 or less.

|

|

Leveling the Field |

|

Now that we've got our image correctly sized, it's time to do some

adjustments. The first, and most important, adjustment we make

is our image levels.

You can think of levels as the amount of output at which the

various pixels differ from each other. We want the parts of

our scene containing our "whites" to be the whitest they

can (without blowing out the highlights, or making them so light

they lose any details in them) and the parts of our scenes

containing our "blacks" to be the blackest they can be

(without losing shadow details).

When most beginners think of such adjustments they think of

Brightness and Contrast, and in a way they are right. But

Brightness and Contrast adjust the levels overall in the image, and

aren't very precise. To get more precision we use the

Image/Adjust/Levels menu command.

Beginner's might be tempted to use Image/Adjust/Auto Levels, but

don't you fall into this trap! Auto Levels is not only very

sloppy, it does color adjustments that you might not want to

do. Since you give up all control when you use Auto Levels,

and since adjusting levels by hand is so very easy, there really

isn't any excuse to not do it yourself.

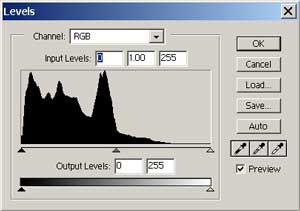

Bringing up the Levels dialog shows you a graph in the middle for

Input levels, sliders at the bottom for Output levels, some

eyedroppers at the right and the ability to save and load in saved

level settings (only really useful if you have a set of images taken

at identical times with the same subject -- a series of rapidly

fired images, for example).

We're only going to concern ourselves with Input levels

here. Output levels probably have their use, but I've never

found one yet. You'll note we have three sliders at the bottom

of the graph. The one at the right controls the highlights,

the one at the left the shadow or blacks, and the one in the middle

controls the midtones (duh).

Adjusting levels is easy and fun with the Preview button

checked. Make sure you can see your image (move the Levels

dialog if you need to) and examine your graph. If it's nice

and even across the board and doesn't drop off dramatically at one

end or the other, you don't need to do anything.

Chances are, however, that one end or the other will be very

shallow, or non-existent. In our example above, it's the high

end that's in sore need of fixing, as it's flatlined quite a

bit. Drag the appropriate slider towards the middle and

watch what happens to your image as you drag.

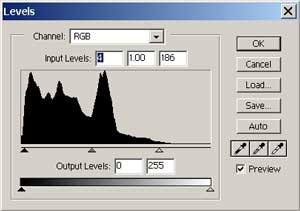

You want to drag your highlights slider towards the middle until

you blow out the highlights (they lose detail). Then back it

off slightly. You want to drag your lowlights towards the

middle until you start to lose shadow detail. That's about all

there is to it -- you can adjust your midtones if you want, but most

of the time adjusting your highlights and lowlights will take care

of the midtones properly. Here's how the above graph looked

after we made the appropriate adjustments:

For a real eye opener after you've adjusted your levels properly

uncheck the preview and note how much difference your adjustments

have made.

This will bring snap and vitality to nearly all

photographs. Every now and then you can't improve an image

with levels -- consider yourself very lucky with that shot.

Other times you may want a very flat shot and not want to juice up

the levels much. It's your image -- do what you want.

There's another trick with levels you will want to be aware

of. There are times that you don't want to adjust the entire image. Here's a

classic example -- an interior with light coming in from the outside

as well as bright lights in the picture itself. want to adjust the entire image. Here's a

classic example -- an interior with light coming in from the outside

as well as bright lights in the picture itself.

If we adjust the levels for the dark lower portion of the image

we'll blow out both the ceiling lights as well as the outside door

lighting. There are many ways of fixing this image -- we'll

leave my favorite technique for last <g>.

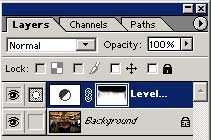

One way we can fix this image is by putting a levels adjustment

layer on the image.

Adjustment layers (Layer/New Adjustment Layer, then choose

Levels) are initially put on the whole image. We adjust for

the parts we want (in this case, the dark lower half), which will

blow out the highlights as we expected. Now we want to

selectively paint out the mask that is applied to the layer.

With the layer selected as our active layer, we choose black for our paintbrush and paint the parts we

don't want to be adjusted -- like with any mask black makes the mask

transparent, white opaque, and levels of gray in between various

degrees. After we've painted the parts we want we then apply

Gaussian blur so our edges aren't distinct, and we end up with

layers that look something like the dialog here. choose black for our paintbrush and paint the parts we

don't want to be adjusted -- like with any mask black makes the mask

transparent, white opaque, and levels of gray in between various

degrees. After we've painted the parts we want we then apply

Gaussian blur so our edges aren't distinct, and we end up with

layers that look something like the dialog here.

This has the effect of applying the levels adjustment anywhere the mask is white, and holding

it back where it is black. So now our picture is correctly

adjusted as shown here. adjustment anywhere the mask is white, and holding

it back where it is black. So now our picture is correctly

adjusted as shown here.

Adjustment layers are good for more than just levels, of

course. Levels, Hue/Saturation, Color Balance and a whole slew

of other useful effects can be applied in this selective

manner. Indeed, using this same general principle there is no

Photoshop effect we can't apply selectively (but we'll cover that in

another lesson).

In the Levels dialog you may have wondered what those eyedroppers

are for. The theory is if you select the rightmost eyedropper

you'll be able to set the white point for your image (and the

leftmost selects the black point). You can try this if you'd

like, just to see what happens, but in actuality if you really do

select the brightest white point and the darkest black point you'll

be doing exactly what Auto Levels does (and it ain't good).

However, there is a very good use for the middle

eyedropper. The middle eyedropper will set your 50% gray

point, and this will adjust your overall color for the image.

If you have an image that has a color cast and you'd like to get

rid of it you can try the gray eyedropper. The trick is to

find a 50% gray in your image -- try clicking a few different places

to see what happens. Sometimes this is the absolute easiest

(and best) way to color correct, but it won't always work (you may

not have a 50% gray or even something close in your image).

It's worth a try, but only after you've adjusted your levels (and

exited the levels dialog) -- you can always undo the damage.

If you are much too advanced for levels you can adjust your image

through the use of curves. Curves are similar to levels, but

have as much in common to levels as levels do to Brightness and

Contrast. There isn't anything you can't do with curves that

you can do with levels, but the reverse isn't true. Once

you've mastered curves you don't need to read anything that I'd

write here about Photoshop.

But Softly

My favorite adjustment technique, one that I haven't shared

before now, is simplicity itself. It works best with a

pressure sensitive graphics tablet, although it can be done with a

mouse (but if you are into editing with Photoshop at any other than

a very casual level, you're going to want a graphics tablet.

For around $100 for the excellent Wacom Graphire,

there's no reason not to have one).

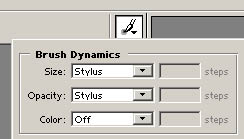

For this trick you apply a new layer from the Layer menu, and set

the mode of this layer to Soft Light. If you have a graphics

tablet set in Photoshop the brush dynamics of size and opacity to

Stylus (see below) -- when you press on the brush you'll control

with pinpoint accuracy the feathering of your brush.

Now when you paint with white you'll burn your image , and black

will dodge it, just like an old time darkroom. If you make a

mistake you can use the erase to erase it. With a graphics

tablet and this technique you can adjust a troublesome image in

seconds.

Which of these do you use? Quite frankly, there are times

it's best to use both. If your image is one that contains

broad areas that need readjustment, a levels adjustment layer is

probably best. If your image is more complicated, with many

areas that need highlighting and lowlighting, the Soft Light will be

the ticket. Master both and you'll be a Photoshop expert!

Note that the true beauty of both of these methods is that until

you actually merge that top layer down, your image is fully

intact. Indeed, it's often helpful to click the eye icon for

that top layer on and off so you can see the difference in your

image. Once you're satisfied you can merge the layers down (or

save as a PSD, which will preserve the layer information).

|

|

USM Forever |

|

The last "basic" tool in the Photoshop photographer's

toolkit is the UnSharp Mask filter, or USM as it's generally known.

We won't go into the technical details as to why here, but all

digital images require some amount of USM adjustment. The only

issues to be discussed are the amount and how to apply it.

There are as many ways to apply USM as there are Photoshop

enthusiasts, and everyone has their own favorite method. We'll

show you the simplest way first and talk about a few others.

The first way is to just bring up the USM filter in the

Filter/Sharpen/Unsharp Mask menu item. Note there are other

choices in this menu to sharpen -- do not use them.

Nothing beats USM and those other methods were put in by the evil

programmers at Adobe just to confuse us.

The Unsharp Mask dialog has three controls: Amount, Radius and

Threshold. You can read all about these in the PS online help,

but I would suggest you start with the settings noted above for high

resolution images (such as from the D30).

As always, you can preview the results as you adjust. Just

make sure you preview at or near your full resolution. If

you're only looking at a 50% window it will be difficult to judge

the effects of sharpening.

About the only time I don't apply a lot of sharpening is for

portraits. I consider the lack of USM in a portrait as the

digital equivalent of the soft focus filter in film photography,

except that it's much more subtle.

Applying USM in this manner applies it to the entire image.

Many PS enthusiasts have noted that, since nearly all of the detail

in an image is contained in the luminance channel, the best way to

apply USM is to only that channel (and thus avoid introducing

artifacts in the color information).

Just what the heck is the luminance channel? It's a channel

of information where the differences in luminance (or brightness)

are contained, as opposed to the channels which contain information

about the color. The easiest way to see luminance is to change

your image to LAB format (Image/Mode/Lab Color) and take a look at

the various channels one at a time.

If you do this you'll see that the L channel (luminance, although

PS stubbornly insists upon calling it Lightness) is what makes or

breaks an image. Apply your USM filter to only this channel

and then convert it back to RGB and you've probably got a better

image than doing it in total RGB.

I say probably only because a difference that makes no difference

is no difference, and if you can't see any difference then it isn't

worth doing. Over the last six months or so I've gone back and

forth between doing USM on the whole image and doing it in LAB only,

and now I'm just not so sure it's worth the effort to convert to

LAB. But try for yourself and make your own judgment.

If this weren't confusing enough, there's still another way of

applying USM to only the luminance channel without switching to

LAB. First, apply the USM as normal to the whole image.

Now (in PS 6 -- it differs slightly in PS 5 and earlier) go to

Edit/Fade Unsharp Mask, and choose Luminosity in the Mode dropdown.

This isn't exactly the same as doing it in LAB, but it's

close. Experiment and see what suits you best (but for

goodness sake use one of them).

|

|

Color Me Happy |

|

About the only other thing I do normally to my images is to apply

color adjustments, as needed. We've already mentioned above

using the gray eyedropper in Levels to fix color casts. You

can also use Image/Adjust/Hue Saturation to fix overall color

balance and saturation (one thing I do for my Epson 1270 is to apply

about 15% more saturation before printing. On screen it looks

garish and pretty awful, but it prints very nice).

While Hue/Saturation is the equivalent of the Brightness/Contrast

hammer, Selective Color is more like using levels. Selective

allows you to add or subtract to various aspects of your hues, using

the best instrument you have, your eyes, to tell you what's best.

And, yes, you can use Curves to fix color as well -- there isn't

anything Curves can't do (they just require a great deal more

skill). |

|

Retouching

Retouching is the art of subtly manipulating an image so that it

looks better than the original. Retouching is not image

compositing, large scale changes to an image, or distortion of an

image. Done right, a retouch job should be so skillful no one

could possibly suspect what was done.

Retouching used to mean getting out an actual pen or airbrush and

working over a printed photograph with ink of various sorts.

It was a process that required huge amounts of skill, and a good

retouching could command a nice salary working in the top magazine

shops.

Nowadays retouching is practically a breeze -- since nearly all

magazines work with digital images at the final end, and since the

software has become incredibly sophisticated at doing nearly

anything you want.

We'll concentrate on the three basic tools of retouching here in

Photoshop: the rubber stamp tool, the smudge tool, and the brush

tool with layer effects. If you master all three of these

you'll be able to do just about anything you need to do when it

comes to retouching.

Using these tools with a graphics tablet (even an inexpensive one

such as the excellent $99Graphire from

Wacom) is much better than using a mouse -- with a tablet you'll be

able to feather your edges with precision and ease using the

pressure of the pen. However, all the techniques we'll talk

about can be done with a mouse (but think about getting a tablet if

you do even a small amount of retouching work).

The Rubber Stamp

The Rubber Stamp is one of the most useful and misused tools in

the Photoshop arsenal. The boon and bane of retouchers, it can

enable you to do nearly anything to an image, including removing

things (like people) which were there originally, and putting things

(like clouds) in your image which weren't there to begin with.

Our problem with this tool lies not in its use -- we'll leave the

debate over image manipulation for another time -- but in it's

misuse. First let's talk about a typical application for it

.

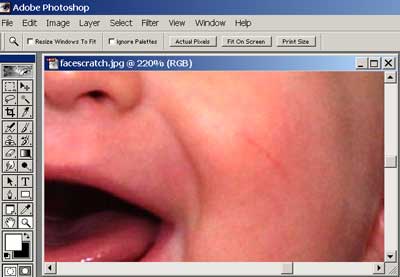

In our image above, the baby has a scratch on his face that his

mother would rather not see in his portrait. We can remove

this in a number of ways, but the Rubber Stamp tool is the easiest

and fastest. First we begin by selecting the tool and, if we

have a graphics tablet, setting it for size and opacity. Now

we sample an area just above the scratch, by pressing the Alt key

down with our cursor in the desired area.

Now comes the part that separates the photoshop men and women

from the boys and girls: to use this tool you do not

"paint" with it. It's not called the Stamp tool for

no good reason. You want to stamp down the areas you wish to

cover, moving your cursor from point to point and slightly up and

down (this will be a lot easier with a tablet). You may

have to shift your sampling point to below the area desired, to

cover more effectively. And this is one of those things that's

much easier to do than to describe. But eventually it will

look like this:

If you paint with the Rubber Stamp tool, no matter how carefully,

you'll end up with tell tale patterns that can usually be seen even

by the untrained eye. These cry "manipulation" more

than any other PS technique, so learn to use the Rubber Stamp tool

right and you'll fool even your best friends (and isn't that what

life's all about?)

The Smudge Tool

While the Rubber Stamp tool can be used to do nearly anything,

there is another specialized tool that's terrific for getting rid of

wrinkles in portraits.

In the old days of photography we used to put gauze in front of

the lens, smear a glass filter with Vaseline, or use a special

"soft-focus" filter to make our glamour portraits of even

older folks look, well, glamorous. We all get wrinkles,

even with the best of genes, and using Photoshop techniques we can

get rid of them far better.

The problem with using any of the old techniques or the modern

equivalents (like using filter/blur on the whole image) is you end

up blurring the important details of the image, like the eyes

themselves. But luckily we can selectively apply a tool that

will remove wrinkles like the way they advertise face creams, and

that's the Smudge tool.

You apply the Smudge tool like you would any paint brush, using

gentle strokes to blur the edges of the wrinkles. Note we're

not going for a completely smooth look here -- that will look odd

when we pull back from the image. The result here looks just

fine at normal magnification.

You might be tempted to use the Blur tool instead of Smudge but

Smudge really works better. But try both to see the difference

and decide for yourself.

Brushing with Color

The last tool in our arsenal is really our old reliable Brush

tool, but using it in a very cool way. It can solve a variety

of problems, but the most common are red-eye and yellow teeth.

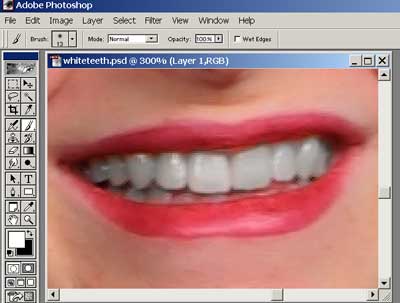

A lot of us suffer from not having perfectly white teeth, and

luckily this condition can be easily corrected. To do so we

bring up another layer on top of our image, and set the mode to

Color.

Now we grab our paintbrush and paint in white on this layer, over

the yellow teeth. Presto, just like the ads say, "You'll

wonder where the yellow went..." Note that we use a

separate layer for this even though we could set our brush to

the Color mode and paint directly on our image. The reason we

do this is simple: if we make a mistake (like removing color from

the lips) it's easier to fix by just using the eraser on this color

layer.

For red-eye fixes you should set your brush to black -- this

works as long as the eyes should be a darker color. For blue

eyes you will need to set it for the appropriate color and work

gently.

|

|

Where

do I go from Here?

There are a whole slew of useful Photoshop tips at the Wacom

tablet site. Even if you don't have a graphics tablet,

this URL is worth visiting.

Follow all the tutorials there and you'll be a Photoshop expert

in no time. |

|